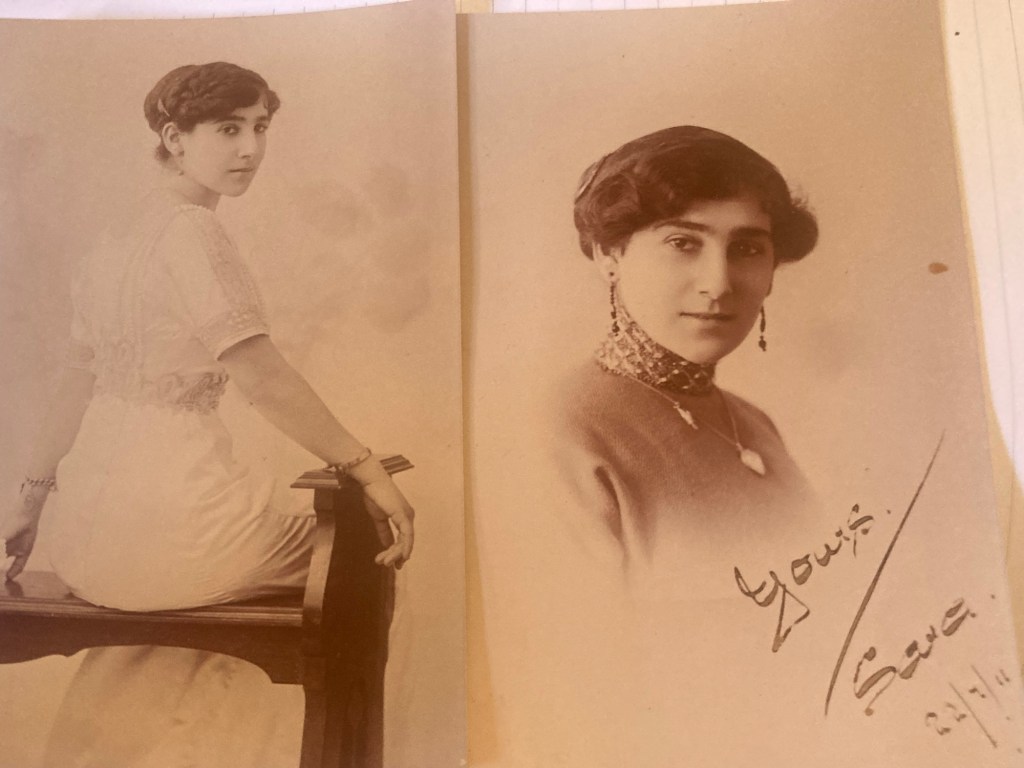

Uncle Bert wasn’t actually my uncle. He wasn’t a blood relative to my Mum or Aunty Doreen,* or to any of their succeeding generations. The family had bestowed the uncle title upon Bert on account of his being married to Aunty Sara. And Aunty Sara wasn’t really anyone’s aunt.

Mum and Aunty Dor cherished Sara, the sole surviving friend of their parents, who died while the sisters were young girls. Dor and Mum loved Sara and honoured her, and tended to her until she died, deaf and blind and loved, at ninety-seven. Uncle Bert died in his eighties, when Sara was still a vital lady of about seventy.

I knew Uncle Bert. He was quiet and gentle. He wore a suit of black material. I recall a black waistcoat. I have a mind picture of a pocket watch and a chain. I don’t remember what work he did. That’s not much to know of an entire living person.

Uncle Bert and Aunty Sara had but one child, a boy, whom they named Basil. I met Basil once. Basil died in his early forties of an overdose of pethidine, an opiate in clinical use at the time. Mum reported Uncle Bert’s reaction. He said simply, My son is dead. Otherwise, Bert took the death in his quiet way, without demonstration. About ten years later, Bert too, died.

All of this came back to me recently while I was decluttering my study. Among odds and ends of my late elder brother Dennis, I found some papers relating to Sara and Bert, and tumbling free from them, a returned soldier’s medal.

Uncle Bert a serviceman! I had no idea. The medal signified facts undreamed. The quiet man in elegant Sara’s shadow had served overseas in the First World War. Had he been in the trenches in France?

Had he, by chance, been gassed?

I never heard the quiet quasi-uncle speak of such.

The little medallion weighed on me. It was not mine to keep. It signified a young nation’s acknowledgement of a man’s service. The medal knew more than I did, and I was one of a very few people still alive who knew Bert Harper. And Bert left no posterity. Time passed, and every day that passed brought me closer to the end of my own life. I worried that the medal, and what it signified, might die with me.

***

A couple of months pass before family matters bring me to Canberra. I pack the medal and I hike my way to the Australian War Museum. As I drive I realise I can’t confidently name my former serviceman. Was Uncle Bert just Bert? Probably not. He might have been Herbert. Or Bertram or Osbert, maybe even Egbert…or Albert; probably not Umberto…

I ask the courteous guard, Where can I research a relative’s war record?

Climb those stairs, Sir, and there, to the left of the café, you’ll find Research.

In Research a young woman sitting behind a large screen smiles a welcome:

How can I help you?

I have a medal left by a relative. I want to find out about his war service.

We can help. Follow me please.

We take a couple of chairs before a second large screen. My companion and guide looks about twenty-five. She has fair hair and a friendly way about her. It transpires that we two will spend a good while together. After about ten minutes I introduce myself. She gives her name – we’ll call her Miranda – and she shakes my hand firmly.

By this stage we have dealt with the question of Uncle Bert’s first name. I gave Miranda my list of suggestions to which Miranda said, If he really was Egbert Harper it will make my day.

Howard: It would make mine if he was Sherbert.

We have already dealt with the medal. It signifies more than the fact of Bert’s service in the AIF. It certifies he had served overseas, had returned to Australia, and had returned alive.There’s a number on the medal’s reverse side. Miranda explains, This number isn’t a serviceman’s AIF number. It just signifies where this particular medal exists in a series of such medals.

Quite a few Herbert Harpers served in the Australian Infantry Forces in the First World War. All are documented. We troll through all the Herbert Harpers.

One Herbert Harper returned with a lengthy and eloquent citation. This Herbert had behaved with conspicuous gallantry, had been decorated repeatedly, and had been killed. My Uncle Bert had not died.

Miranda looks over to my covered head: What was his religion?

Jewish.

None of these Herbert Harpers put Jewish as their religion. Many Jewish recruits did not admit Jewishness. Usually they’d write C of E for convenience. What was his date of birth? Where was he born?

I thought he was born in Perth. His date of birth? I do not know.

I call my eldest cousin. He knew the Harpers before I did. He should know more. Eldest Cousin knows less than I. He says, I remember Uncle Bert, but I never knew he went to war. I don’t remember much about him Doff. I’m afraid I’m useless.

Miranda asks where Bert was born. Mum told me the Harpers and her parents had all been friends in Perth. I assume that’s where Uncle Bert comes from. Miranda finds a Herbert Harper in the National Archives who enlisted in the AIF in Perth, in 1916. This Bert was five foot, seven inches tall, which Miranda informs me was close to the median height for a male serviceman in WWI. His full name was Herbert John Harper, his stated religion is Church of England. Miranda adds, All personal details are self-reported, their truthfulness self-attested. My grandfather, for example, gave his age as twenty when he signed up, but he was only seventeen.

I happen to know a few solid facts about Uncle Bert. He married in the Perth Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation. I know this from his ketubah, one of the documents that I stumbled upon when I found the medal. An Orthodox rabbi will not marry you unless you can prove you are Jewish. Customarily, you do this by producing your parents’ ketubah.

This a Jewish marriage certificate, written in an ancient Aramaic formula.

Uncle Bert and Aunty Sara were definitely Jewish, not C. of E.

As I muse on Herbert John Harper of Perth, my phone rings: It’s the Eldest Cousin. Doff, I’ve googled Bert. He was born in 1885. He wasn’t from Perth, the family lived in Malvern, in Alice Street – where my nephew lives today!

I deliver this intelligence to Miranda, who checks the First World War Embarkation Roll of all Herbert John Harpers. Here she finds a Herbert John Harper who enlisted in the 44th Australian Infantry Battalion on December 30, 1915. He is listed as single, a commercial traveller, aged thirty years. His home address is 123 Raglan Road, North Perth. Herbert’s next of kin is his father, who lives in Alice Street, Malvern.

This Herbert is our family’s Uncle Bert. He is indeed, prosaic Herbert, not Egbert, not Sherbert. Before enlisting, he works as a commercial traveller, that is, an itinerant salesman, the humble line of work of many Jews at the time, (and in my own family, up to the 1960’s).

Sydney Myer was one such. Myer Emporia are his legacy.

So it’s at the end of 1915, when Uncle Bert is well beyond his callow days, that he joins up. Uncle Bert didn’t join the great romantic adventure of the War at its outset. Why join just now? I learn the War is going very badly for Britain and her Allies at the end of 1915. Britain has just withdrawn from Gallipoli, is retreating in Salonika, and has withdrawn from Macedonia. The British Commander in Chief in Flanders and France has resigned and been replaced. On December 30, the armoured cruiser, HMS Natal explodes, with 400 lost; and Herbert John Harper, commercial traveller resident in Perth, joins up. His Service Number in the 44th AIF Battalion is 804. Miranda informs this number will stay with Private Harper wherever he serves, and in all records. He might be seconded to a different unit, but he’ll remain Number 804.

Miranda directs me to the First World War Nominal Roll where we find an Embarkation Date of February 7, 2016, and a date of return to Australia twenty-two months later, in December 2017. She tracks his movements between those dates to Great Britain and subsequently to France.

Now, there’s normally no discharge so long as hostilities continue. Exceptions occur in the case of Dishonourable Discharge and in the cases of illness and injury. Why does Herbert Harper, 804, come back early?

Miranda finds Bert’s disciplinary record. He has misbehaved, being Absent Without Leave. This is pretty grim reading. Miranda finds the details: “CRIME: Absent from Reveille.” “Punishment: Admonishment.” By way of context, Miranda gives the story of her grandfather when he was AWOL. He nicked off somewhere for 4 or 5 hours. Grandfather’s punishment was docking of eight days pay! Our Private Harper, 804, has no pay withheld.

So this delinquency would not explain Bert’s early return. Was he injured or otherwise unfit? We turn to Bert’s Medical Record. We read his Certificate of Medical Examination upon enlistment: He does not present any of the following conditions, viz. : –

Scrofula; phthisis; syphilis; impaired constitution; defective intelligence; haemorrhoids; varicose veins, beyond a limited extent; marked varicocele with unusually pendant testicle; inveterate cutaneous disease; chronic ulcers; traces of corporal punishment; or evidence of having been marked with the letters D. or B.C.; contracted or deformed chest; abnormal curvature of the spine; or any other physical defect calculated to unfit him for the duties of a soldier.

Bert’s later records state he is discharged medically with Hyphasis. This is not a diagnostic term I learned at Monash Medical School between 1963 and 1969. I have not heard of it since. Neither has my colleague, Dr Google. The copperplate writing is very clear: the word written is clearly HYPHASIS. Does the recording officer misspell KYPHOSIS? This condition is not rare and used to be called hunchback. I don’t recall Uncle Bert having any spinal deformity. What is more, in his examination upon enlistment, Private Harper, 804, showed no abnormal curvature of the spine. His spine was straight and his “testicle not unusually pendant.”

Miranda moves on and shows me Herbert Harper’s request, in 1917, for a War Pension. Quite promptly he is awarded a pension of forty-five shillings per fortnight. Is this handsome or meagre? Quick enquiry suggests the equivalent in Australian currency is $270.00. By way of comparison, today’s Australian Disability Pension pays $1149.00 per fortnight.

These discoveries explain the somewhat unusual fact of Aunty Sara conducting her own business. Sara Harper owned and ran a women’s clothing shop in elegant Ackland Street. That precinct was known as The Village Belle. Aunty Sara’s was not a thrift store. It sems likely Aunty Sara worked because Uncle Bert could not.

Miranda has been musing: Herbert Harper is found fit to fight in December 2015. He remains fit for embarkation two months later. He is shipped to Britain and onward to France. After twenty-two months, he enters hospital in Australia, is soon discharged, and after only a few months, is awarded a pension. He must have been injured or otherwise medically unfit.

I wrack my medical brain. A formerly straight spine will collapse into a ventral hunch if one or more vertebrae collapses. Commonly this occurs in postmenopausal females who have osteoporosis. Cancer in a vertebra can also cause this, as can tuberculosis of the spine. Gunshot injuries might also destroy vertebrae, leading to collapse into kyphotic deformity.

We find no record of spinal injury or disease in Private Herbert Harper, just the enigmatic word, Hyphasis.

So, here is Herbert Harper, unmarried on enlistment, a bachelor still. The War continues and he takes a wife, Sara. The couple are blessed with a son, who grows, becomes addicted and dies. Uncle Bert dies, and much later, Aunty Sara follows. Their line comes to an end. I recall my Mum corresponding with a woman in Perth who was connected to Sara. I think she was a niece on the non-Harper side. I don’t know her name. She was older than I, and eligible therefore, for extinction.

By the end of 2026, I estimate there might be twenty people at most who are alive today and who knew Uncle Bert. Most of that number are themselves aged. When all of our cohort departs this life, there will remain of Uncle Bert no memorial but the medal. And perchance, this record.

This troubles me. A quiet man, a patriot, who put his life at hazard and lost his health; who knew the joys of marriage and fatherhood; who lost his only son. Insignificant to me in my childhood, he matters to me now. He signifies.

A realisation dawns. Uncle Bert had a father, William Harper of Alice Street, Malvern. Did William father additional children? Did he have siblings? Who knows? – flocks of Harpers probably exist, unaware of their connection to Herbert John Harper, AIF, 804. Unaware too, of the medal that is rightfully theirs.

This little memoir is posted here in the hope it will find its way to a descendant or relative of William Harper, who lived in Alice street, Malvern, Victoria, in the early 20th Century.

(*Aunty Doreen, on the other hand, was sister to my Mum, authentic and authenticised.)