There is nothing sensible about running a marathon. It is a difficult thing to do. There appears to be a physiological upper limit of tolerance to distance running. At some point around 35 kilometres most runners experience a steep falling away in efficiency. Sports physicians suggest humans were not made to complete a marathon distance, which is a little over 42 kilometres.

People die running marathons. While most do not die, or even suffer serious or lasting harm from the marathon, even a single death is one too many, given that there is no need, no practical purpose, to completing the full distance.

Running marathons is not even an efficient means to attaining physical fitness; you can achieve equal fitness with brisk walking as with running, and the risk to life and joints is far lower when you walk.

Earlier in my own marathon running ‘career’ (a suggestive term: it isn’t a career in the sense of something I do for a living; something that runs off the rails is said to ‘career’) I had the opportunity to go for a training run with the great Rob De Castella in Boulder, Colorado. Earlier I had discussed with sports doctors my experience – common among marathoners – of slowing radically over the final 7 kms of the race. The physicians had suggested that human beings weren’t meant to run that distance: there was the physiological limit I referred to earlier. De Castella, himself a sports physiologist, was educated by the Jesuits at Xavier College in Melbourne.

After our run, exquisitely taxing at that altitude, I put the same question to De Castella. It was the Jesuit rather than the physiologist who answered: “If human beings gave up just when something became difficult we wouldn’t achieve very much, would we?”

That is the answer. In that nutshell is the reason that Paris and London will see tens of thousands compete in their respective marathons next weekend. It is for that reason that we love to do what we hate. I have run and hated and loved forty three marathons, in places as diverse as Boston and Alice Springs. I hope to run more.

If the marathon runner defies physiology the marathon watcher defies sense. In all weathers she stands outdoors and watches an endless, anonymous train of athletic mediocrities, watches for hours on end, feeding these strangers everything from jelly snakes to orange segments to fried snags. At her side her small child claps everyone who lumbers past. Her teenage daughter holds a placard that reads: YOU ARE ALL KENYANS.

My mother knew nothing of sport. Her lack of knowledge stood her in good stead for the marathon, indeed for any sporting event she witnessed. At the time of the Melbourne Olympics Mum took us kids to the fencing. She knew only that the swords were not lethal weapons, that the fencers’ precious eyes were safe. Those facts were enough for Mum. She barracked for the victor, she urged on the vanquished. She loved them both equally and generously.

IN 1956 the Olympic marathon course led from Melbourne to Dandenong and back to the MCG. The route followed the Princes Highway, which passed the end of our street. Mum stood and cheered every contestant on the way out and waited for their return. By that stage the runners were jaded and strung out. The leaders too were well separated. As the runners passed our street an American was leading. Coming second or third and looking tragic (in a way I came to recognize in my adult life) was a New Zealander. “Good on you, Kiwi”, were Mum’s words from the empty kerbside, a distance of only a couple of feet from the runner. Mum’s sweet urgings encouraged the runner, who visibly accelerated. Later Mum would say, “I helped him to win.” In fact the Kiwi did not win – Mum was no stickler for small facts – but she put her finger on a larger truth: he was a winner: he finished. He did his best.

It is in Boston that the runner and the spectator most truly meet. There the amateur runner is embraced by the uncritical spectator. She too is an amateur. She hasn’t a clue who is favoured to win; she has twenty seven thousand favourites; she loves them all. A literal amateur. Extraordinary statistic: of a population of three million persons in the greater Boston area, one million spectators come out to watch the race. The spectator comes out and she remains there, cheering, clapping, waving placards, uselessly feeding, encouraging every last pathetic struggler, every finisher, every champion. These three, as she well understands, are one and the same.

She was there, this ignorant dame, when I sailed past her, full of hope, energy, crowd fever and coffee early in last year’s race. She was there as I struggled up Heartbreak Hill. She was there in Boylston street to see the winners – man, woman, wheelchair champions (both genders) – as they crossed the line. She was there when the first bomb went off. Was it the first bomb or the second that took her life? I do not know.

I know this: she will be there again this year when the race is run again; there in her thousands at the start, in her tens of thousands in the middle, in her weaving, praying throngs through the weary late stages, there among the ecstatic crowds that squeeze joyously at the kerbside as crazed runners find speed for the final gallop along Boylston Street. She’ll be hoarse and weeping as the untalented race along those cobblestones in their ragtag glory, arms pumping, heads high, fists aloft as they cross the line.

And what of the runners? We are wiser now. Inevitably, sadder. Running – that senseless frolicking of supposed adults will never be the same.

A record field will contest Boston in 2014. Terror will enjoy its limited success – some attention for a cause, or as seems likely in this case, no clear cause; some increased security, some minor oppression of amenity and civic liberty – but the lovers of Boston will meet and embrace as they always do, at this, their festival.

Running, our ceremony of joy, now sanctified, will always be the same, that familiar pointless folly.

Tag Archives: death

Melbourne’s Daughter

Deep with the first dead lies London’s daughter

(Dylan Thomas)

The newspaper article was short, buried at the bottom of an inner page: Man Sought in Child Death was the headline. Ambulance officers were called to attend an infant who was not breathing. They found injuries described as Non Accidental. They detected a feathery heartbeat and commenced resuscitation and brought the baby to hospital.

Following further treatment the baby underwent scans of the brain. These demonstrated Injury Incompatible with Life. Police wished to interview a man in connection with the matter.

Nearly forty years ago I became intimately familiar with that hospital. At the age of fifteen months our youngest child was treated there for Aplastic Anaemia. I had learned enough of this invariably fatal disease at medical school to dread it. Over three miraculous days and three intense nights nurses and doctors worked on our infant as if she were their own. Three days following her admission our baby was home again, her condition in spontaneous remission. It never recurred.

I witnessed at that time what a friend describes as the operation of ‘an edge’. He says a hospital like that is a line where the worst and the best meet and rub up against each other. The worst, he suggests, is the suffering or death or loss of a child; the best is the application of skill and care and discipline in opposing the worst. The line where the best strains against the worst is a hospital like this one. My friend describes this as ‘OUR best’. By extension the loss or suffering of the child is OUR worst. I mean we are all implicated.

What must we learn from those pregnant expressions: ‘Non Accidental Injury’ and ‘Injury Incompatible with Life’? Horribly intrigued I sought more news in the next day’s paper. I found nothing. For the first time in my life I went to the news on-line. I googled ‘non-accidental injury to baby’. Straight away I was sorry I had done so. Case after case, headline after headline, BABY AFTER BABY, the web told of the slaughter of our very young in Australia. RecoiIing, I quickly ungoogled. A phrase from the biblical book of Numbers came to me – ‘a land that devours its children.’

Another friend is a senior doctor at that same hospital. He is the person with whom the buck stops, it is he who has to confront the adults in whose watch a non-accidental injury has taken place. Too often the x-rays show the many non-accidental fractures that have healed or half-healed or never healed in a baby’s short tenure. He sees the scans that show the brain bruised and bleeding from multiple sites. Calmly, civilly, he must direct questions to the adults. He says, ‘Your baby has been injured in ways that cannot occur by accident. Can you explain the injury to me?’ The adult partnership fissures along one of many fault lines, the truth emerges. And the truth is braided of many rotten strands. The perpetrator – sometimes more than one perpetrator – is almost never the simple monster we like to imagine. The perpetrator too often had himself been monstered – his life fractured, his brain contused by one evil or by another or by many.

I read, over the days that followed, a scattering of further details, most of them horrible beyond my imagining. And finally, this: the injuries being incompatible with life, the parent of the child had agreed the doctors should turn off the machines. But before that, she donated the baby’s organs. Injuries incompatible abruptly became compatible with saving half a dozen young lives.

I described babies who are killed as OUR babies. I felt, as I read Helen Garner’s, ‘This House of Grief’ that the three murdered boys were in a real sense Garner’s children, they were mine, they were all our children. And in my moments of google horror I felt the same shock of personal responsibility.

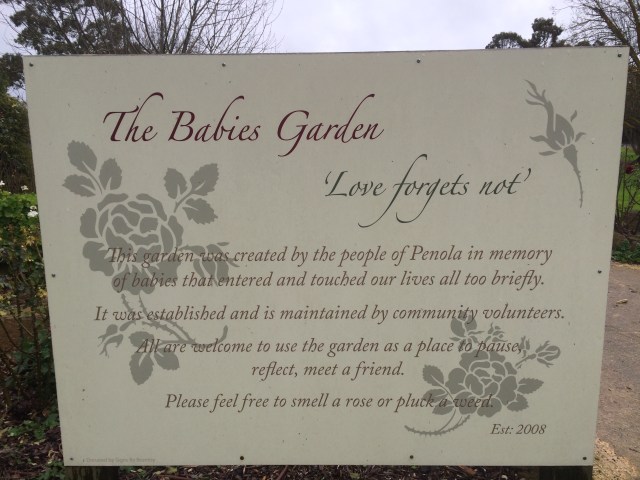

In the small South Australian town of Penola people built and tend a park to remember their babies lost.

Happy Concatenation

Mr Menzies, as he was then, used to report to Parliament upon his return from

The Prime Ministers’ Conference in London. He’d introduce his report with, ’By a happy concatenation of circumstance I happened to find myself in London for the Conference at precisely the time of the Cricket Test Match at Lords…’

I read this in the ‘Age’ newspaper and looked up ’concatenation’. I have kept the word close, generally unused, for the half century since.

By a singular concatenation of circumstance, today Jewish people around the world observe Shushan Purim on precisely the date of Good Friday. Yesterday we had the concurrence of Purim with Shrove Thursday; and the previous day the Jewish Fast of Esther coincided with the fast of Ash Wednesday. That’s how calendars concatenate.

By a happy concatenation of circumstance, while riding home through the park yesterday I overtook another cyclist, emerging into Commercial Road just as she did. From a long way back I saw first the yellow jacket. Gaining, I noted her tall, erect carriage in the saddle, her fair pony tail, her fair skin. Emerging from the park, with eyes only for the vehicular traffic ahead I had no time to sight her face.

I crossed the road and halted, waiting for the red light to turn. A voice emerged from a blur of yellow: ‘Howard? It is Howard, isn’t it?’ I had time now to take in that fair face, to recognise the features and that voice. A voice of a singular quality, a soft voice, with a sweet self-echo, as of a bell. I knew that voice.

‘Hello, Camilla.’ My voice would have carried surprise and delight.

‘Where are you heading, Howard?’

I indicated.

‘Me too,‘ she said, ‘I’m headed to St Lucy’s to pick up Joe.’

Our ways were the same and we rode together and caught up on the events of ten years: the growth of her son Joe (one of my babies), the decline and deaths of her parents and mine; and the premature loss of a brother, in each case only a little older than ourselves.

I told Camilla about Dennis. I mentioned the regret, my uncompleted mission, that marked my time with Dennis and that surfaces years after his dying, in my dreams. When I spoke of my brother’s dying Camilla’s face fell. Her voice a deeper bell.

‘I lost a brother too. I loved him.’ Camilla’s voice thrilled and her face shone as she spoke of her brother. ‘His name was Tom. He was a twin. He lived to forty-nine then he died. I don’t know what of. He was disabled. I loved him. We spoke on the phone every day. Every single day.’

‘What was his disability, Camilla?’

A smile, a half shrug: ‘Do you know, I can’t say exactly what he had and I don’t know what he died of. I suppose now you’d call it cerebral palsy. He was born with it. He was just my brother and we loved each other. We were together every day as children, back in the Mallee. Then I left and studied and moved interstate, but it was still the same. We spoke every day. I loved him. Often we’d speak a few times in the one day.

‘Tom was the second twin, you know. Second twins are often sicker…but you’d know all about that.’

I wondered about Tom’s disability: ’Was it physical or intellectual, or both?’

‘It was both. Do you know, I’m buying the old family home. In the Mallee. It’s a sentimental thing, a bit silly really.’ Camilla laughed: I’m buying out the other twin. I want the house. Tom and I lived in it, Tom lived there all his life.’

We arrived at St Lucy’s. Children thronged in the grounds, ignoring the scores of parents who waited outside. They played and shouted and pushed and grabbed each other in the high spirits of the coming holiday, while Lucy’s eyes searched for Joe and my mind played on brothers loved and lost. On a brother who called me every day, often two, three times a day.

Shouting goodbyes children drifted from the gates to their parents. A tall child, erect and fair, came into view. He greeted Camilla in a sweet voice, soft, with a sort of self echo.

[I wish readers variously a joyous Shushan Purim, a holy Easter, and always, always – happy concatenation.]

The Departure Lounge

Driving my sister to the airport earlythis autumn morning I looked about me and took in the mists and the mellow fruitfulness. My younger sister is not young. Shortly we would embrace, say goodbye, we’d look forward to next time and we’d both know, ‘next time carries no guarantee’.

I recalled a trip I took to that airport with Mum. I described it to my sister: “This all happened before Mum suffered her strokes. She was not young but could still travel independently. My plane to the outback was due to depart at 10.00. Mum’s inter-city flight was scheduled an hour later. I dropped Mum off at her lounge in a shower of kisses and embraces, and raced to my own lounge. Over the Public Address I heard, ‘The flight to Woop Woop has been delayed. We expect to board passengers at 11.00 and to take off soon after. We regret the inconv…’ I raced back to Mum.

‘Hello darling. How lovely to see you!’ Mum’s face was lit by a smile of mild astonishment. Time’s exigencies always surprised Mum. I began to explain and she took my hand and began to stroke my volar forearm. She said, ‘Aren’t we lucky, darling.’

I felt lucky: here we were, quiet together among the hubbub, heads bent to each other, tasting our found time. A thought came to me: ‘Mum, we two have always been sitting in our Departure Lounges, waiting for our separate flights. We both know one day we’ll have to leave, we just don’t know when. And we can’t really know who’ll leave first.’

Mum nodded. Her walking fingers patrolled from my wrist to the inside of my elbow, back to the wrist then back again. Her touch was light. I thought of early memories of Mum’s touch, of the times when she bathed Dennis and me. We both spoke at once; ‘Your skin feels so soft and smooth.’

As our hour melted away we didn’t say much.

The Public Address commanded us to part. Knowing and accepting, we parted in gentler shower of kissing and holding. Knowing and accepting and feeling very lucky, we took our separate flights.”

Dread

The child’s body dropped like a stone from the platform to the track. One moment a boy stood securely on the platform, the next he was a flash of movement downward, vertically, feet first from the platform. No cry, no sound, just a flash of grey school shorts and white school shirt. Standing on the platform a moment earlier he looked small, perhaps a first grader. I did not know him.Now he was an absence, a silence.

I peered downward and could not sight him. I leaned out , far forward, near to my own tipping point. I saw an unsuspected shelf beneath the platform – small enough for a small body, too small for mine. Perhaps the train would miss him, pass him by. Who knew?

The moment after he dropped extended horribly forward into Time. I did not know when the train would come. I was the nearest adult. It would have to be me.

I awakened with a small cry. I sat up in the dark and shook my head, shaking away the image of a small body in a new uniform, passing from safety into the plain where I must step forward. I and only I. The dread lingered long after the unreality – there is no boy; there is no hazard – settled in my mind.

The dread lingered. I think it was not the dread of my dreadful death, but the dread I would delay too long.

***

What triggered this unearthly vision before the rapid movement of my eyes? Two days earlier I rode my bike home from work. As I pedalled hard past the boys’ school a small body in a white shirt exited a gate just before my flashing wheels. I jammed on the back brake and the front. The hurtling bike stood on its end and stopped. I did not. I fell at the feet of the boy like a stone. He stood, shocked as he regarded the body of an aged man lying at his feet.

Among the Lesbians – Ronja and Friends

A young woman from Alice Springs wrote a letter to her father recently. In real life the young woman is a songwriter, singer and filmmaker. Her husband is a human rights lawyer. Recently the couple has been spending some time among the recent arrivals from Syria in Lesvos. You need to have a picture of the writer: imagine an underfed, undersized jockey. Imagine that jockey is entered in a race in which she is obliged to carry a second jockey on her back: Ronja – that’s her name – would be that second jockey. As you will see, Ronja has single-handedly flung English spelling into a bizar new age. She writes:

Dadda,

Mine is a strange life right now. I am currently in the Mayer of Lesvos’ office trying to get atms installed in the registration camp Moria (one of the worst places in the world currently). A 5 month baby died there 2 days ago from freezing in the snow, we have up to 5,000 people there most nights sleeping in the snow and rain, not enough food and there are fights and riots daily. The stories of this continue. Rape, gangs, gypsies scamming the etc. it’s a mess.

I wake every day and deal with the 70+ volunteers I am responsible for. The admin staff of the foundation all went on holiday 2 weeks ago, so I suddenly became the personal assistant of the woman in charge. Melinda from Starfish Foundation. She was in the Financial Times magazine last year as the number one woman (ahead of Michelle Obama).

A part of this means deciding the vision of the foundation, as well as meeting with the heads of the 100, or so NGO’s (unhcr etc) on the island. I love meeting these people and going to meetings where information is shared. I may never get to work like this again, so am relishing the moments.

She trusts me now and so I work also as a personal sounding board. She wants me to move here and work under her, but we’ll see about that.

I came to clothe and feed people. Instead, I write legal documents, structure how we can implement the best care for refugees and am trying to get funding for special projects: such as information distribution and programs for unaccompanied minors.

I came to clothe and feed people. Instead, I write legal documents, structure how we can implement the best care for refugees and am trying to get funding for special projects: such as information distribution and programs for unaccompanied minors.

I have also been writing music for the foundation for fundraising. I’ll send you the videos when they are posted. That’s been great fun! There are real popstars and so many famous people on this island. Film stars, film makers, musicians and artists. I played my ukulele to Ai Weiwei last weekend and then made a small speech. That was bizar! I think he liked it and he thanked us for our work.

Still, I go a bit crazy not having any time to myself and with Shaan. Shaan is in full swing as camp coordinator on behalf of Starfish- you know what he is like.

The only reason I can write now is because I am waiting in the Mayer’s office.

I am very very interested in what is happening with the unaccompanied minors here in Europe. I met a family of about 50 members from Afghanistan that changed my life 2 weeks ago. Two girls 14 and 10 travelling with a brother who was 17. In the same family a boy 16 travelling mainly with a cousin in this 20s. These three children are legally unaccompanied, so would have been separated, detained and kept in Athens until they each reached the age of 18. They were with family who loved and cared for them, but this was not recognised. They were the most beautiful people and I become very close to the 16yr old boy Mujtaba, who now talks to me every few days from Germany. There is more to this story.

Furthermore, I hear from people who have worked in this area that the children are not properly supervised and are not given proper resources. Most of these children end up running away and getting lost in Europe trying to find their family.

There is also child trafficking happening. We have seen this ourselves.

I want to come back in July and see if I can get into the child compound at Moria camp. One of the good things about meeting all the big wigs is that I have met people who can get me into these areas. The police are in control of the compound, so to be let in is an absolute privilege. If I can get in I want to see if I can come back and run art and music workshops next year. Anyway, we’ll see. It’s all just thought currently, but Melinda knows this is my passion and will help me get permission and money I believe. Right now, my heart and imagination are captured… Also, Shaan will most likely be employed by the foundation in the next few months. AND this crisis is not going anywhere, so neither are our potential roles. Who knows, we may end up living in Greece for a year or two. How surreal.

I better go. The Mayer just arrived. Love you xoxoxoxoxox

Yizkor

I found the photograph I had been missing. It was found, as most of my misplaced objects are, precisely where I had placed it; in this case it was safely at the bottom of my backpack. I wanted it for remembrance.

The photo sits in its small oval frame. It shows two small boys sitting side by side. Their cheeks have been pinked by some process of photographic enhancement common to photos from the ‘fifties. One boy sits cradling a large teddy bear. The boy’s face is a narrow oval, his expression unsmiling, alert, guarded, attentive to the photographer who is an adult in a frightening world controlled by adults. The second boy, taller, wider, rounder, has a fuller face, topped with wavy titian hair. He has the daughter of a smile on his face. His is the image I have sought, this the face of the person I wish to hold in remembrance.

The portrait conveys much of what I wish to hold: the elder boy is Dennis, his parents’ firstborn, my brother. His destiny is here to be read. It’s all here – firstborn, male, cherished; good-natured, close to his younger brother – and fat. In this photograph Dennis must be about four. In less than sixty years he will be dead.

***

Literally translated, the Hebrew word yizkor means ‘he will remember’. Over the recent Festival period I recited the yizkor prayer for my father, my mother, my wife’s father; and for Adrian, my consuegro; and I remembered them all tenderly. It was only when I prayed for Dennis that I cried. I cried for the protective brother I could not protect, for the always-advising brother I could not advise, for the firstborn who worshipped this usurper as a hero.

Dennis did not ask to be born fat. He did not ask to be born first. He loved his father as his father loved him – not wisely but too well.

Immoderate in all he did Dennis loved his younger brother immoderately. I miss him, I pray for his rest as I pray for my own.

Dinner with Some Old Teenagers

Word reached me, and when it came, it came obliquely. My writer friend in England, Hilary Custance Green, forwarded a letter that had reached her by way of one or another of the virtual media. ‘I wasn’t certain what to do with this,’ she wrote, ‘I thought it might be spam, but I decided to forward it, just in case.’ The writer of the letter asked Hilary if she could forward it to her old doctor. The letter bore strong feelings that had brewed and bubbled within the writer over years.

‘Dear Dr Goldenberg, I don’t know if you remember me but I remember you and I have wanted to contact you for a long time.’ There followed the remarkable declaration that my actions had saved the writer, now aged fifty-five, when she was a girl of seventeen. She owed her present happy life, she wrote, to my intervention, as well as the help of some others around that time.

The letter, and the memories it evoked, thudded, jolted within me. Yes I did remember the girl, firstborn of three, trapped in a hell where her violent alcoholic father abused all in the home. I remember the face, fair skinned, the coronet of fair hair. And her brave, fugitive smile.

I read on, and as I read the girl’s name came to me, a diminutive in the Australian way, never Anna but ‘Annie.’ Annie’s father was a helpless, hopeless drunk, and when drunk prone to unpredictable extremity. Annie would await his return from the pub with dread, hoping he’d keep away, hoping helplessly her mother and sisters would be safe. She’d have fled the family home long before but father had screamed and waved his gun at her. His words – ‘If you try to leave I’ll shoot you and the others and myself’ – shocked me. Uselessly, helplessly, I trembled for the child. The child confided she never brought a friend into that house, for fear of the shame. She told me these things, forty years ago, and I recognised a further shame, even deeper, Annie’s self-disgrace to be ashamed of her own father.

In her letter Annie reminded me of the Saturday night she finally escaped. Father had drunk all that day and into the night. Annie sheltered in her bedroom but when father burst in she ran from him, wearing only her nightclothes. Father screamed behind her, ‘You’ll never come back into this house, girl!’ The girl walked through the early hours, avoiding exposed places. She found herself in the deep dark of a railway culvert and, terrified in that blackness she decided, ‘This is where I’ll have to sleep from now on.’

Annie wrote, ‘I walked to the clinic and laid down and waited there for you to arrive. You’d always been kind and understanding. I knew you worked the Sunday mornings. I didn’t have anywhere else. You took me in when you arrived and after work you drove me home so I could safely collect some clothes. Then you drove me to a refuge.’

Annie’s account of that last-first morning was only dimly familiar. I felt small stirrings of pride, and a tenderness for the girl in the nightdress. Much stronger was my shock as I realised I had not thought of her since the ‘rescue.’ Annie had disappeared from the days of those busy years. She had lived, thrived, suffered reverses, sought salvation, recovered, blossomed, become the assertive woman her mother could never be, married happily and raised children, good citizens, and now saw grandchildren. Forty years and no thought by her wonderful caring doctor. That child had come into her own and that doctor had reached his prime and passed it.

Perturbed, I wrote to Hilary to thank her for sending word, for her gift.

The word found me in the outback. I wrote to Annie, giving my phone number and told her I was anxious to speak to her. My phone rang as I rode my bike across the railway line. I dismounted and answered and the voice said it was Annie and for twenty minutes I listened to her narration of the events of a turbulent life. We agreed we’d meet after my return from the outback.

In the exchange of emails that followed a second voice entered, followed by a third, then a fourth. Later a fifth and a sixth made contact. The writers, all roughly contemporaries, had been my patients in their teenage years. Each bore a burden of recollection which pressed now to be discharged.

Three women, matrons now, waited for me at the restaurant. I opened the door to faces that shone. I saw three faces of girls in their teens. I stepped forward and found myself clasped. Lined faces kissed mine, ample bodies held me close.

We sat. The women said how young I looked, I said how good they looked. The past was with us, the past with its beauty and its horror. The past, reverberating with friendships I had forgotten and the three had remembered.

How had I forgotten?

The waitress came, hovered, departed. Again she came and we promised we’d soon choose and order. It was not soon. Forty years here, twenty there, so much event, so much life. Babies – it turned out I had delivered them – were now adults, some even parents.

The waitress returned. Jerked into the present we ordered.

Girls Numbers Two and Three are sisters. I asked after their parents, immigrants, older than me by ten years, proud people, beavers in the general community and within their own. Mum was alive, still vibrant – ‘and fat, like all of us!’ Shrieks of laughter. And Dad?

‘Dad’s fat too, and dementing. The grog; it’s Korsakov’s.’ The speaker is Number Two, now a nurse. In the care of their aging parents she’s the officer commanding Number Three and their brothers.

Both Three and Two were married when I last knew them. They’d married matching buffoons, agreeable blokes when sober, not often sober, not often enough agreeable. Three spoke: ‘Even before we married I saw how my father in law treated his wife. He’d tell her she was stupid, shout at her to shut up when she spoke. One time I saw him belting into her – he was full as usual. I froze. We never saw that. Mum and Dad would drink a couple of gins after work but they never got nasty. Not like that.’

Memories returned to me of the mother in law. A tall trembling lady, her face pink and scarred, she’d address me in a soft trembly voice, describing symptoms I could never fathom, never cure. Now I understood.

‘It wasn’t too long before Robbie was getting aggressive like his Dad. He’d go to the pub after work, get full, drive home drunk. I had my first girl, then the second. I thought, “No. This isn’t what I want for them, not what I want them to see.“ I rang Robbie and I said, “Don’t hurry home you drunken bum. Your wife and your kids have split.”’ Peals of laughter from Three, far the widest at our table. ‘Did he ever hit you?’ – I wondered. ‘Lot’s of times, but I’d belt him too!’ More jolly mirth. Three sits opposite me, her great arms a gallery of art in brilliant reds. Finer tattoos crawl upward from her bodice, another spiders around her neck.

‘Weren’t you scared, leaving him?’

‘No.’ The thought is a stranger to Three. She stares at my unexpected question. ‘There was no future there. I got up, took my girls and went.’

Did I raise an eyebrow? I certainly wondered at her resolve, her clarity. Her fearlessness. ‘Yeah, money was tight. I got a job and I worked and I looked after my girls. They’re good. Their blokes are lovely. And the three of us, we’re very close. Like me and sis here.’ The two women looked at each other and smiled.

Two reminded me: ‘I was a mother at nineteen. Got married. You delivered my babies, Howard. I was in labour, terrified, not knowing anything. You got up on the bed beside me and stroked my back.’ Did I? Nowadays the Medical Board would caution me for this sort of thing. They’d require me to undergo Education.

Two continued: ’You know everything about us. You’ve seen all our vaginas!’ Careless in their merriment the girls showed none of the self-consciousness that saw me look down and blush. ‘I’m diabetic now,’ continued Two. ‘But I’m good. After I left my husband I worked as a nurse, you know, State Enrolled. When my kids were adult and near-adult my partner encouraged me. He said, “You’ve always wanted to study. Do it.” So I did. I studied nursing at Melbourne University. Boy that’s a gap – from Victoria Uni to Melbourne. But I did well…’

‘Got Distinctions’, Three’s voice was proud.

‘I did all of it on scholarships. I had to perform. They can take the scholarship away if you get bare passes. Now I’m specializing in Mental Health, in charge of the ward. I love it.’

Three told me how she too had always worked in health, in administration. She described without bitterness how, after eighteen years, her institution had managed her out of her job and into retirement. ‘Now I write poetry. I go to Creative Writing classes. And every Wednesday I post a poem on Facebook. Wednesday is the hump of the week. I call my readers, my “humpies.” Here’s this week’s poem’. Three handed me her phone where I read her tidy quatrains. The verses spoke in anticipation of this gathering, in praise of the poet’s doctor, his kindness, his understanding. Blushing again I came across a ‘Like’ in response. The author of the Like was Four, another ex-teenager whose family I’d been close to. Four wrote, ‘I remember how Dr Howard comforted me when Karen died.’ Another thump.

I remembered Four, a striking girl with olive skin, tight black curls, a smile that made you feel like singing. I remembered Karen, Karen who was lost, that sparkling child. Karen was in the car that drove to the pub in the bush hamlet twenty kilometres distant from my country practice. The pub filled the young driver up with grog and watched him drive the carful of friends home. How many died when the car missed the bend? Four? Five? Karen was extinguished in that crash. I remember speaking afterwards with Four. Was she the only one I was trying to comfort? I think I was trying to comfort myself too. A year or so later another young driver killed himself driving home from the same pub. His passenger suffered a fractured neck, became quadriplegic. From that time until left I doctored the human wreckage. And my rage burned against that pub. I nursed a futile wish to close it down.

***

The girls spoke of the men in their present lives. Annie had formed a lasting union with Ian that prospers still. She showed me the album her family made for her fiftieth birthday. Here were Annie’s mum, Annie at fifteen, Annie’s own grown children, Annie with Ian. I saw a tall man, angular and strong-looking, with a craggy face. Two and Three spoke warmly of their own blokes. All three had known some duds but the ‘girls’ bore no hostility to the male race. When, at the conclusion of the evening, Ian turned up to drive Annie home he towered over me. My not-small hand was lost in his handclasp. Instantly likable, solid as a wall, he smiled and I felt gladdened for Annie.

Two asked Annie: ‘Have you ever seen your father again?’ Quietly came the reply: ‘I always vowed I never would. Then four years ago he wrote to me, to all of us, Mum, my sisters. He said he was dying, in Mallacoota. His heart was failing, from the grog. He wanted to see us. Mum wouldn’t come, neither would my sisters. But I thought, “He can’t hurt me now.” So I went. He talked and he talked, poured out his side of our lives. He lay on the bed and asked me to lay by him and cuddle him.’

I looked at Annie, my eyes wide.

‘I thought, “He can’t hurt me now. He’s old and he’s dying alone.” He’s got a partner but she’s not his blood. It’s not the same. I climbed up beside him and I held him. We laid there together for a good while. After a couple of days I went home. He died two weeks later.’

Two Recipes for a Long Life

Recipe One

(Yvonne Mayer Goldenberg, 8 June, 1917- 7 June, 2009)

Eat only foods rich in butter and cream. Avoid any food that requires chewing, especially vegetables. (My mother was frightened by a vegetable as a child and never came near one again.)

Relax. Do not rush. Shun punctuality.

A lady who possesses the skill of changing a flat tyre should conceal such knowledge. ‘Why deprive some gentleman of the opportunity to behave chivalrously?’

(Mum believed in chivalry. As a child when instructed by her teacher to use the word ‘frugal’ in a sentence, Mum understood ‘frugal’ to mean one who saves. She wrote: ‘A lady was walking by the sea. A strong wind lifted her up and flung her into the waves. She could not swim. She saw a man on a white horse: “Frugal me! Frugal me!”, she cried. So the man leapt into the waves and frugalled her. And they lived happily ever after.’)

Rejoice in your kin; they are life’s benison to you. You will not have them forever. (Mum’s parents died in her childhood. Left with her younger sister in the care of her beloved grandmother, Mum cherished all her descendants with promiscuous undiscrimination.)

Smile. Nothing is so serious that it should furrow your brow – unless it hurt your little ones.

Talk to strangers, visit their countries. Walk the earth without fear. People are good.

Forgive your children their naughtiness. Indulge your adolescent children in their self-absorbtion. They owe you nothing; they give you all.

What you cannot cure you must endure – with a smile. (Mum’s hip was shattered in her twenties. For forty years she walked in pain, with a marked limp. She did not think to complain. Pain did not interest her. Likewise the disabling strokes she suffered in her last decades. ‘A stroke is boring’, she said.)

Decorate your life. Eat every day from your best china; use the good cutlery. (Which day will be better than today? Who better than the family to enjoy these things?)

Raise your boys to help. (‘Why should I be your kitchen slave? There is no pride in being a parasite.’)

Sex is good, sexual pleasure very good. Never boast of your conquests. Use a condom. (These last two dicta were delivered to her sons before the age of nine.)

Feminism is a mistaken impulse. (It arises from the absurd notion held by some that a woman could possibly be inferior to a man in any particular.)

Never open someone else’s mail.

Read. Meet new words. Look up every one in the dictionary. Read everything – the classics, the junk mail, the cornflakes packet.

Don’t fear death. Speak of it freely. (‘Death is a part of life, darling.’)

Do not fear harm. Fate is kind. Clothe your young in love but do not over-wrap them. Harm probably won’t befall them. Entrust them to the care of the universe.

Do not fear at all.

Recipe Two

(Myer Goldenberg, 5 December, 1909 – 10 September, 2003)

Fear everything. (Dad witnessed his friend die of electrocution when the stays of his yacht struck power lines. He operated on trauma patients without number. These events made him warn his children of the injuries that result from inattention or lack of care. One warning would never suffice. No number of warnings could suffice.)

Do everything. But take care. Sail, drive, use power tools. Never wave a knife around. Safety first. Safety last.

Fear nothing and no-one. No task is beyond you, no skill too hard to master, no knowledge beyond your reach, no person to be feared.

Eat vegetables. Overboil them first.

Be firm with children. Demand they meet your own high standards. Don’t coddle them in their minor ills. But if real harm come near, cross the country to protect or repair them.

Don’t let your children off lightly. But protect them ferociously from attack by an outsider.

Cherish your kin. Honour your parents. Honour your ancestry.

Honour your work.

Work hard. Keep going. Do not weaken.

Do not run marathons.

Be worthy. (Dad idolised his parents, particularly his father. Through his long life Dad wished always ‘to be worthy’. He meant worthy of his own father. Even in his eighties Dad fretted he was not worthy. I ached when I heard him speak so.)

Forgive. Never hold a grudge. Speak your anger then reconcile.

Never forget or forgive one who hurts your young.

Keep your words clean. Do not say ‘bum’, never say ‘bloody’. Forget ‘dick’. When you belt your thumb with a hammer, allow yourself ‘YOU BITCH!’

Exercise. Where you could drive, choose to walk. Walk fast. Your children can run to keep pace.

People are good. Life is good, health a blessing. Protect it with injections.

Do not fret about germs. They build resistance.

Breast feed. (‘They’re not just there to fill jumpers’).

Cuddle your children. Kiss them – the boys too. And not just in private.

Pass on your faith. Drill your young in ancient ritual and practice.

Tell the children Bible stories. Read those stories with passion and conviction. Pass on your heritage with love and pride.

Be proud. You are as good as anyone else. And no better.

Be authentic. Do not fear being different. Respect yourself and others will respect you.

Love your children. Succour them in your old age as you did lifelong when the need was real.

Show tenderness. A man can be soft and still be strong.

Tell the truth. Demand the truth. Nothing is more sacred than your word. Nothing nourishes better than trust.

Don’t arrive on time. Arrive early.

Never open someone else’s mail.

Work hard. Save for a rainy day. (Dad worked very hard. He practised medicine to the age for ninety-two and a half. To the end of his life he saved for a rainy day, never feeling the heavy rain upon him, never knowing the time had come to take shelter.)

Sing. Sing loudly. Sing with your children. Sing table hymns with your children on Shabbat; sing loudly in synagogue; sing sea shanties, sing nonsense songs. Opera is grand but Gilbert and Sullivan are brighter, more fun.

The compass needle on your boat flickers; at the poles the compass fails. Know your own True North. Follow it.

Embrace the sea. Sail, fish, and sing. Travel by boat at night, navigating by stars, chart and compass. Do not fear the sea. Never take it for granted.

Be vigilant. Experience the rapture of your mastery of an alien element.

Do not fear. Relax. Never relax your vigilance.

See the beauty, smell the ozone, relish this given world.

Thrill to the cresting wave, the heeling sailboat.

Surrender to the windless calm. Experience tranquillity.

Feel the caress of the sun, the bracing breeze. Both are good.

Give thanks. Be thankful.

Love your kin. Nourish them, work for them protect them, nurture them. Demand resilience.

Be brave. Be true.

When all is said remember the love.

Writing as Healing

The mother of identical twin boys sent me this story by Ranjava Srivastava.

“Losing my twin baby boys for ever changed the way I treat my patients.

I will never know the kind of doctor I would have become without the searing experience of being a patient, but I like to think my loss wasn’t in vain.

‘My obstetrician’s tears stunned me but also provided immediate comfort. They normalised the mad grief that had begun to set inside me.’

Around this time 10 years ago, I was poised to start my first job as an oncologist when personal tragedy visited in a way that would forever change the way I would practice medicine.

I had returned from my Fulbright year at the University of Chicago, blessed with only the joys and none of the irritations of being pregnant with twins. Landing in Melbourne, I went for a routine ultrasound as a beaming, expectant parent. I came out a grieving patient. The twins were dying in utero, unsuspectedly and unobtrusively, from some rare condition that I had never heard of. Two days later, I was induced into labour to deliver the two little boys whom we would never see grow. Then I went home.

If all this sounds a little detached it is because 10 years later I still have no words to describe the total bewilderment, the depth of sorrow and the intensity of loss that I experienced during those days. Some days, I really thought my heart would break into pieces. Ten years later, the din of happy children fills our house. But what I have found myself frequently reflecting on is how the behaviour of my doctors in those days profoundly altered the way in which I would treat my patients.

An experienced obstetrician was performing my ultrasound that morning. Everything was going well and we chatted away about my new job until he frowned. Then he grimaced, pushed and prodded with the probe, and rushed out before I could utter a word. He then took me into his office and offered me his comfortable seat. Not too many pregnant women need a consultation at a routine ultrasound.

“I am afraid I have bad news,” he said before sketching a picture to describe the extent of the trouble. I thought for a fleeting moment that my medical brain would kick in and I would present him with sophisticated questions to test his assertion that the twins were gravely ill. But of course, I was like every other patient, simultaneously bursting with questions while rendered mute by shock.

I was well aware that doctors sometimes sidestepped the truth, usually with the intent of protecting the patient. I knew he could easily get away with not telling me any more until he had more information but I also knew that he knew. I read it in his face and I desperately wanted him to tell me.

I asked the only question that mattered.

“Will they die?”

“Yes,” he said, simply holding my gaze until his tears started.

As I took in the framed photos of children around his office he probably wished he could hide them all away.

“I don’t know what to say,” he murmured, his eyes still wet.

Until then, in 13 years of medical training, I had never seen a doctor cry. I had participated in every drama that life in bustling public hospitals offers but never once had I seen a doctor cry.

My obstetrician’s tears stunned me but also provided immediate comfort. They normalised the mad grief that had begun to set inside me. Yes, the doctor’s expression said, this is truly awful and I feel sad too.

“You are sure?”

“There is a faint chance that one lives but if you ask me, things look bad. You know I will do everything I can to confirm this,” he said.

The obstetrician had told the unflinching truth and in doing so almost surgically displaced uncertainty with the knowledge that I needed to prepare myself for what lay ahead. I had test after test that day, each specialist confirming the worst. I think I coped better because the first doctor had told the truth.

Two other notable things happened that week. Among the wishes that flowed, another doctor wrote me an atypical condolence note. His letter began with the various tragedies that had taken place that week, some on home soil and others involving complete strangers. “I ask myself why,” he wrote, “and of course there is no answer to why anyone must suffer.”

Until then, everyone had commiserated only at my loss – and I was enormously grateful – but here was someone gently reminding me that in life we are all visited by tragedy. All the support and love in the world won’t make you immune to misfortune, he was saying, but it will help ease the pain.

Finally, there was the grieving. I lost count of the pamphlets that were left at our door to attend support groups, counselling sessions and bereavement seminars but we were resolutely having none of it. My midwife called me out of the blue – it was a moving exchange that taught me how deeply nurses are affected too. But I didn’t need counselling, I needed time. I valued the offers but I knew that my catharsis lay in writing. I wrote myself out of suffocating grief, which eventually turned to deep sadness and then a hollow pain, which eventually receded enough to allow me to take up my job as a brand new oncologist. How I would interpret the needs of my patients was fundamentally altered now that I had been one myself.

Cancer patients are very particular about how much truth they want to know and when. I don’t decide for them but if they ask me I always tell the truth. A wife brings in her husband and his horrendous scans trigger a gasp of astonishment among even the non-oncologists.

“Doctor, will he die from this?” she asks me.

“I am afraid so,” I answer gently, “but I will do everything in my power to keep him well for as long as I can.”

It is the only truthful promise I can make and although she is distressed she returns to thank me for giving her clarity. Sometimes honesty backfires, when the patient or family later say they wanted to talk but not really hear bad news. I find these encounters particularly upsetting but they are rare and I don’t let them sway me from telling the truth.

Oncology is emotionally charged and I have never been afraid of admitting this to the very people who imbue my work with emotion. I don’t cry easily in front of patients but I have had my share of tears and tissues in clinic and contrary to my fears, this has been an odd source of comfort to patients. In his Christmas card, a widower wrote that when my voice broke at the news that his wife had died he felt consoled that the world shared his heartbreak.

It can be tricky but I try to put my patients’ grief into perspective without being insensitive. It’s extraordinary how many of them really appreciate knowing that I, and others, have seen thousands of people who are frightened, sad, philosophical, resigned, angry, brave and puzzled, sometimes all together, just like them. It doesn’t diminish their own suffering but helps them peek into the library of human experiences that are catalogued by oncologists. It prompts many patients to say that they are lucky to feel as well as they do despite a life-threatening illness, which is a positive and helpful way of viewing the world.

I will never know what kind of a doctor I might have become without the searing experience of being a patient. The twins would have been 10 soon. As I usher the next patient into my room to deliver bad news, I like to think that my loss was not entirely in vain.”

………

I read this story with alarm. It made me feel anxious because I have and love a pair of identical twin boys. I felt involved because, like the writer’s doctor, I am a doctor who cries; and like the writer, Dr Srivastava, I am a doctor who writes. Finally we two are products of the same medical school (Monash) – Dr Srivastava graduated at the top of her class, in the present century, I graduated at the opposite end of my class, in antiquity (1969).

A final point of commonality was her reassuring remark that ten years after her doctor wept her home is full of the noise of happy living children.

I found the piece helpful. Dr Srivastava identifies and untangles the strands of her experiences with surgical deftness. Her doctor weeps, her colleagues show support and care and empathy and she heals. As a trained observer, the writer dissects her experience of grief, lays out its anatomy and reflects upon its organs and parts.

Like the writer, I find relief and understanding in the act of writing. I suspect that a part of this relief results from word search. The writer is obliged to seek the precise word for the experience. In my case this forces me to test and taste a number of words. Perhaps a dozen words might work more or less passably, but the acts of searching, of choosing, of trialling, help me to clarify what my feelings were not quite like. I mean I discover what I mean. Perhaps this functions as a working through, a self-conversation, something between analysis of an experience and re-imagining it. In my case too, the pleasure of words is an aesthetic joy that comforts me.

Medicine is a pursuit conducted with the living in the shadow of death. It is a pursuit packed with anxious questions: what is wrong with me, will I die, what can be done, will it hurt, how much, how will I know the answers, when will I know? This crying doctor feels the patient’s fear and his own and has to know the border that divides the two. My fears are for the patient, of the patient, of failure, of failing a person of flesh and feeling. My fears include the terror that strikes me when I see my patient slipping away, the knowledge of my mortal inadequacy.

The writer who lost her twins precisely names the elements in her emotional experience. With remarkable poise she traces the costs and the benefits of the loss. So coherent are her reflections I could feel myself learning as I read. I learned about her life and her work, how the two are not the same but never severable. I learned more of how a doctor feels, who she is, who I am.