Following my recent blog post titled ‘Unnatural Medicine’ one correspondent bothered to respond thoughtfully and at considerable length. As you will see from the passage below (excerpted from his comments) he writes insightfully and with strong feeling. I quite understand that intensity; health is both a personal and a universal concern. Further, at the head of its hierarchy and ruling our fate, standing over us, exciting our awe and our resentment, are the doctors.

…On the other hand we see leaders in western medical practice dismiss Chinese medicine, for example, as quackery and voodoo medicine. Despite clinical trials clearly demonstrating the effectiveness of acupuncture, for example, many Scientists declare that there are no such thing as “meridians” in the human body as their existence has not been clinically demonstrated. The hypothesis is dismissed despite evidence gained from the applied testing that they do. Further, many assert that all forms of Chinese medicine, sometimes including acupuncture, should not be considered “real” medicine. (This includes senior doctors advising government and insurers.) Yet this practice has 4,000 years of accumulated clinical practice, is taught in major teaching hospitals in China and practiced daily by doctors in conjunction with “modern” western practice. Numerous clinical trials of diagnostics, treatments and herbal concoctions have been conducted, which are generally dismissed in the west, often merely because they are not available in English. When they are available, the results are howled down because there is no critical mass of such research available. Yet the Chinese pharmacopeia is yielding impressive results in western labs in the treatment of everything from common infections to malaria and cancer. Why is there such resistance to the science of Chinese medicine?

With the social and economic power of the western pharmaceutical industry we continue to see western medicine practised with an emphasis on the provision of drugs as first recourse in treatment. So pervasive is this that you have written about patients who want the prescription of a drug, any drug, rather than wanting to hear a more complex story of how to achieve health and of some doctors who support this approach. We have a culture of “science” where alternatives can often be dismissed and where pharmaceuticals are pushed to the frontline of treating almost any and every condition. Incidentally, my father peddled Debendox – among many other drugs- to doctors in the 1960s and ’70s for the treatment of morning sickness and later associated with birth defects. It was given to me as a treatment for travel sickness. Hard science and its practice makes mistakes.

Please forgive my self indulgence in presenting my rant, Howard. I know your musings are often light-hearted and exploratory of deeper things. But I guess my point is this: there is an ideological spectrum in medical practice, which can be said to range from “natural” to “unnatural”. There is medical practice that works with the “natural” processes of the human, which includes an understanding of diet, exercise, psychology, history, social conditions, the environment, etc all having their effects, good and bad, on human lives. In common parlance “natural” usually refers to seeing patients as people first, human beings subject to and part of nature in never-ending cycle of birth, life, death, repeat (depending on your belief). My experience of your practice puts you in this camp. Do as little harm as possible, be cautious, be curious, respect the person, do not jump to conclusions or easy answers, respect the life process. Sometimes trauma means offering treatment (or not) that may cause damage or harm. A difficult choice.

There is also practice that does not respect the human, does not give value to patient’s experience, knowledge of their body, etc. There is a dominant (moot?) practice of prescribing western pharmaceuticals first and asking questions later in the next 15-minute consultation a week later. This well-documented practice is disease focussed and knows little of health, except as the “absence” of disease. This “unnatural” practice is characterised by a focus on the disease or condition, of which the “patient” is merely the subject. Treat the disease, not the person.

This spectrum lies at the heart of current debate and power struggles within medicine and in policy regarding human health. It has enormous implications also for all policy that focuses on the human species as somehow separate from “nature”, implicitly subject to different rules, with or without the possibility of divine intervention to protect us from ourselves.

I find myself highly stimulated by my correspondent’s comments. I’m bursting with an accumulation of thoughts and feelings of my own, musings and speculations. I suppose these have gathered and grown within me over a lifetime in medicine. (It has quite literally been a lifetime: born into a household that accommodated my family and my father’s medical practice, I grew up in medicine. I was weaned on milligrams and speculums.)

My own feelings about western medicine and doctors are as mixed as anyone else’s. I am old enough to need the services of my doctors quite frequently, while still young enough to be doling out medical services to others. Macbeth cries, ‘Throw physic (medicine) to the dogs. I’ll none of it!’ And in a few cryptic words the Talmud declares: ‘”tuv harofim le’ge’hinnom” – the best of doctors can go to hell.’

Does medicine have an ideology? If an ideology is a system of beliefs or ideals or principles, I believe medicine does have an ideology. In the practice of that ideology I see the best of medicine, and in its abuse, the worst. That worst is the exercise of power for its own sake, a petty parochialism, a readiness to denigrate what it does not understand; and, in budget season, a hypocritical piety.(“No, no, no, Mister Treasurer , you must not cut, peg or regulate our fees – or our patients will suffer.’) The best is seen in your doctor’s service of ‘scientia cum caritas’, knowledge with loving care.

For me it is the ‘scientia’ which is the hard bit. Your good doctor is a scholar: the word means ‘teacher’, ‘master’, ‘wise one.’ That scientific doctor applies himself to the evidence. He suppresses his own human hankerings, his romantic leanings, his wishful thoughts. That doctor brings to his work a rigour, an austerity, a devotion to the pursuit of demonstrable truth. When I am sick I truly need that science; and your good doctor brings that to my bedside.

Let me give you an example. While working in the Emergency Department of Alice Springs Hospital last week I watched while five doctors worked to save a man who had been found at a remote roadside, unconscious and convulsing violently. The man was tall, strongly built, apparently athletically fit. His mountain bike was found lying near him. Unable to tell us how or what or when, his powerful body defied his absent mind as it jumped and threw itself around. I stood, quietly appalled, watching a man fifteen years my junior, disconnected from mind, at the threshold of the void.

The doctors watched him for signs. Acutely attentive to which limb moved, which did not; how his pupils reacted to a pencil beam of light; whether and how strongly he responded to voice (initially he’d stir; later he did not), and to a painful stimulus. Here was a biological organism in a near agonal state. The doctors looked up to study the lines and waves and numerals on the screen. How strong is his heartbeat, how effective his circulation? How much oxygen are his lungs delivering to the circulation and – critically – how high is the blood pressure? The readings were elevated above the norm. I misgave and pointed out the elevation to the Team Leader. ‘That’s good,’ he said. He explained that the damaged brain was much more vulnerable to low blood pressure than high. The outcome, he explained, was worse when pressures were low. ‘The outcome’: two words pregnant with knowledge, with meticulously gathered and tested and scrutinised evidence. Tough minds had obeyed tough rules in the gathering of that evidence; now smart scholars would deploy this in our immediate emergency. I witnessed dry science at the service of hot blood.

It was imperative to control the seizures and to treat pain. Surely he had pain – he’d had a fall, presumably at speed, his skin was torn from his body, gravel and mud grimed his raw wounds – and he was vomiting forcefully on arrival. He must not be allowed to vomit lest he aspirate and block his lungs.

Next the man’s respirations must be controlled. He’d be paralysed and placed on a respirator. He’d become utterly defenceless. The very doctors who would overcame his defences must become his protectors.

To all these ends, all of them critical, all of the utmost urgency, strong drugs would be used – opiates, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxant drugs, anaesthetic agents, anti-emetics. Doses must be calculated minutely, effects monitored, dosages re-calibrated. The precise numbers of milligrams and micrograms would determine whether this man would live, would walk, would think, would speak, read, laugh or love. ‘Will this man ever get back on his bike?’ All lay in the hands of these scientific doctors.

But how to calculate dosages? Unable to weigh a stuporose man threshing his own body, the doctors had to guesstimate. Too much opiate would lower blood pressure and endanger the damaged brain. Too much anti-convulsant would do the same. And both classes of chemicals might suppress breathing. The anaesthetic drugs must be adequate to paralyse him (to allow intubation and the use of the respirator), but again these agents can defeat their own purpose.

So the doctors injected morphine, eagle eyes upon oxygen saturation and respiratory rate and blood pressure. They injected metoclopramide to prevent vomiting that morphine so readily triggers. They deployed three different anticonvulsants, in doses nicely titrated, before they were able to control the fitting. Now came the intricate business of intubation, the act of introducing a breathing tube deep into the throat in defiance of every natural reflex and physiological objection; this procedure, a pas de deux of surpassing intensity, saw all present hold their breath in unconscious imitation of the patient, now paralysed, whose breath was held from him by chemical restraint. Now the tube was guided truly, now oxygen supply was resumed, hypoxia reversed. All breathed out.

Our patient would never know how medical science saved him. How doctors had used just enough of every hero molecule, how they had threaded that narrow path between his own injuries and the potential harm of their remedies. How every drug might poison him. And of the race of his life, the literal counting of seconds where every second counted, the quietly hectic passage of time when he arrived as quivering meat and was so soon stable. Safe!

Equally deep was the pool of knowledge that detected the cause of all – no, not head injury, not brain contusion, not spinal cord injury – a heart attack had thrown this athlete, engaged in a mountain bike race in unseasonal heat, into coma and convulsion at the threshhold of death.

So, yes, western medicine has its ideology. Last week I saw that ideology save a human person. Clearly I am in awe of that sort of intellectual discipline which is so far above and beyond my suburban skills.

By way of contrast we who practise by instinct, by intuition, must tread the shallows of organic disease, even as we grope in the deeps of human suffering. You cannot afford to indulge our speculative modes of medicine when your damaged organs call out for science.

In the earliest years of my practice I felt frustrated when patients informed me of the advice they’d received from alternative practitioners. Those healers would declare to my patient her spine was out and they’d put it back; they’d looked in her eyes and found her pancreas was sick and they’d cured her with herbs. Not with drugs, no, never with drugs. Those healers prescribed detox diets for the liver, cheerfully unaware that the liver detoxifies all. They told my patient they knew what was wrong, where I knew I did not, where no doctor could – in any scientific sense – know.

I came in time to respect the achievements of these practitioners. My patients felt better for seeing them, encouraged, confident in their recovery. I wondered how this could be and it came to me that the naturopath gave the patient the gift of an unrushed, attentive hearing. The amplitude of time, the emphasis upon natural healing, the resounding vote of confidence in the forces of the natural body helped the patient materially. I realised how intuitive, how insightful, how respectful was this practitioner. I recognised in the naturopath the healer I wished to be. But there was one difference, ineradicable: I never heard a patient quote the alternative practitioner confess ignorance or impotence. Free of the shackles of constraining science, the practitioner never said three words that I need to use every day. Those three words are: I don’t know.

I am pretty confident I have by now offended some readers. This is always a risk with the trenchant expression of strong opinion, of ideology, if you like. And it is not only western doctors who hold an ideological position. I consider it natural to humans, perhaps universal, to cherish convictions about health and its care. These convictions too encompass values, traditions, emotional needs. Mine are distinctively my own. Every distinct human will differ. Expressing my full thoughts on these subjects might offend seven billion humans.

Nevertheless I propose to write a series of short pieces which might include:

Why some doctors resist and resent alternative medicine;

‘Thou shalt not kiss thy patient’ and other absurdities.

Why I recommended acupuncture for a patient whom doctors could not help.

Why doctors prescribe medicines: Big Pharma, big mamma, bad sicknesses;

My Debendox daughter.

In writing on these matters I expect to relieve myself of strong feeling, long pent. And after all that I will scarcely have responded to my correspondent’s weighty concerns.

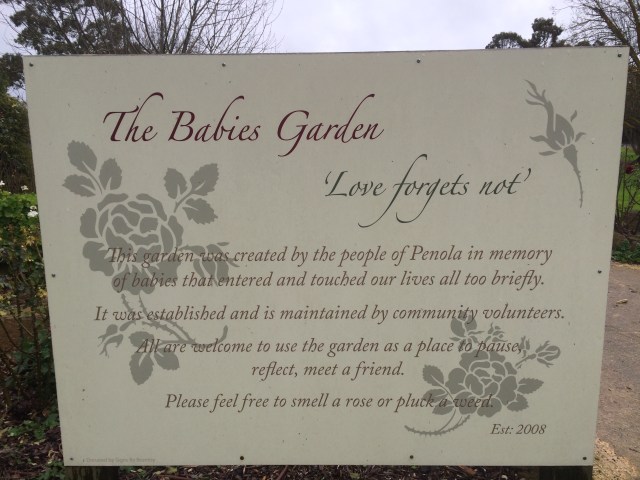

One final vignette before I let you go. In 1972 I joined a rural practice where I worked happily for almost thirty years. Around that time I met a squat jolly man and his slim jolly wife. The couple had three small daughters and I became their family doctor. They were a devout family, members of a small local congregation of a church which is possibly the most widely respected by the secular majority in this country. They wore their piety tactfully – neither crucifix nor yarmulke nor hijab declared publicly their private faith.

From time to time Mother brought the little girls, slim, elfin presences with smiles that sweetened my day. They’d sit on my knee while I discussed their condition their mum. In time they grew up and left their small home town. One of the three, whom I’ll call Sarah, returned and introduced me to her fiancé, a member of Sarah’s church. The two had decided on a career as ministers to the youth in the service of their church. Soon they would marry and take positions in a distant city interstate.

When I saw Sarah next seven years had passed. Her father had died of complications of orthopoedic surgery. Her face shone with grief and pride as she introduced her batch of three small children to me. Slim like Sarah, all with biblical names, they played at our feet as we spoke of their grandfather, that squat jolly man, and of his passing. Sarah and her husband petitioned the church for a posting in Melbourne to be nearer the family.

They settled in an outer suburb on the far side of town and I saw nothing of them for about three years, when Sarah turned up in my waiting room. Delighted and surprised I listened as Sarah told me of the strange and slow development of her second child, a boy. ‘Jeremiah might have autism.’ We talked. I told Sarah I was no expert in that condition. She seemed to know that already. She wasn’t after diagnosis, but counsel and for that it was to her old family doctor she turned.

Years passed. Once again I was delighted one day to discover Sarah in my waiting room. She was the final patient of my morning. By chance I had no more patients to see for the next hour and a half.

‘Hello, Sarah. What brings you here?’

‘Howard, this morning in the shower I found a lump in my left breast.’

‘Does it hurt?’

‘No.’

‘Do you have chills, a fever?’

‘No, it’s not mastitis. I weaned Benjamin a year ago.’

I examined Sarah’s left breast. Her slim body habitus made the lump easy to find. It was a hard lump, a little larger than an almond. I felt the opposite breast: normal. I probed her axillae. There, in the left armpit I felt a second lump, also hard. I tried to hide the dread I felt.

Sally looked up at me, searching my face: ‘Can you feel the lump?’

‘Yes. It’s a worry. Please get dressed and we’ll talk.’

We talked for an hour. We talked of the probable cancer, of its possible spread, of treatments, of specialists – who, where, when? Sarah asked, ‘Do think I’ll be cured, Howard?’ I did not think she would. I said the signs were worrying and I feared the worst. Sarah looked down and rummaged in her handbag for her hanky. She sat quietly, tears rolling down her cheeks. She dabbed her eyes and cried some more. The hanky was a sodden ball in her hand. She blew her nose and said, ‘I’m not frightened for myself. The children… they’re so young.’ Fresh tears followed.

At length it was time to finish. I stood up. On blind instinct, driven I suppose by hard feeling, I said, ‘Sarah, stand up.’

She did so. I stepped forward, took her in my arms and hugged her. She hugged me back, hard. I dropped my arms but she hugged on. And on. At length she released me. She took a deep breath, found a small smile and said, ‘That’s what I crossed Melbourne for, Howard.’

I never saw Sarah again. Her surgeons wrote to me from time to time. Eight years after her doctor took her in his arms and breached medical ethics, Sarah died.