Word reached me, and when it came, it came obliquely. My writer friend in England, Hilary Custance Green, forwarded a letter that had reached her by way of one or another of the virtual media. ‘I wasn’t certain what to do with this,’ she wrote, ‘I thought it might be spam, but I decided to forward it, just in case.’ The writer of the letter asked Hilary if she could forward it to her old doctor. The letter bore strong feelings that had brewed and bubbled within the writer over years.

‘Dear Dr Goldenberg, I don’t know if you remember me but I remember you and I have wanted to contact you for a long time.’ There followed the remarkable declaration that my actions had saved the writer, now aged fifty-five, when she was a girl of seventeen. She owed her present happy life, she wrote, to my intervention, as well as the help of some others around that time.

The letter, and the memories it evoked, thudded, jolted within me. Yes I did remember the girl, firstborn of three, trapped in a hell where her violent alcoholic father abused all in the home. I remember the face, fair skinned, the coronet of fair hair. And her brave, fugitive smile.

I read on, and as I read the girl’s name came to me, a diminutive in the Australian way, never Anna but ‘Annie.’ Annie’s father was a helpless, hopeless drunk, and when drunk prone to unpredictable extremity. Annie would await his return from the pub with dread, hoping he’d keep away, hoping helplessly her mother and sisters would be safe. She’d have fled the family home long before but father had screamed and waved his gun at her. His words – ‘If you try to leave I’ll shoot you and the others and myself’ – shocked me. Uselessly, helplessly, I trembled for the child. The child confided she never brought a friend into that house, for fear of the shame. She told me these things, forty years ago, and I recognised a further shame, even deeper, Annie’s self-disgrace to be ashamed of her own father.

In her letter Annie reminded me of the Saturday night she finally escaped. Father had drunk all that day and into the night. Annie sheltered in her bedroom but when father burst in she ran from him, wearing only her nightclothes. Father screamed behind her, ‘You’ll never come back into this house, girl!’ The girl walked through the early hours, avoiding exposed places. She found herself in the deep dark of a railway culvert and, terrified in that blackness she decided, ‘This is where I’ll have to sleep from now on.’

Annie wrote, ‘I walked to the clinic and laid down and waited there for you to arrive. You’d always been kind and understanding. I knew you worked the Sunday mornings. I didn’t have anywhere else. You took me in when you arrived and after work you drove me home so I could safely collect some clothes. Then you drove me to a refuge.’

Annie’s account of that last-first morning was only dimly familiar. I felt small stirrings of pride, and a tenderness for the girl in the nightdress. Much stronger was my shock as I realised I had not thought of her since the ‘rescue.’ Annie had disappeared from the days of those busy years. She had lived, thrived, suffered reverses, sought salvation, recovered, blossomed, become the assertive woman her mother could never be, married happily and raised children, good citizens, and now saw grandchildren. Forty years and no thought by her wonderful caring doctor. That child had come into her own and that doctor had reached his prime and passed it.

Perturbed, I wrote to Hilary to thank her for sending word, for her gift.

The word found me in the outback. I wrote to Annie, giving my phone number and told her I was anxious to speak to her. My phone rang as I rode my bike across the railway line. I dismounted and answered and the voice said it was Annie and for twenty minutes I listened to her narration of the events of a turbulent life. We agreed we’d meet after my return from the outback.

In the exchange of emails that followed a second voice entered, followed by a third, then a fourth. Later a fifth and a sixth made contact. The writers, all roughly contemporaries, had been my patients in their teenage years. Each bore a burden of recollection which pressed now to be discharged.

Three women, matrons now, waited for me at the restaurant. I opened the door to faces that shone. I saw three faces of girls in their teens. I stepped forward and found myself clasped. Lined faces kissed mine, ample bodies held me close.

We sat. The women said how young I looked, I said how good they looked. The past was with us, the past with its beauty and its horror. The past, reverberating with friendships I had forgotten and the three had remembered.

How had I forgotten?

The waitress came, hovered, departed. Again she came and we promised we’d soon choose and order. It was not soon. Forty years here, twenty there, so much event, so much life. Babies – it turned out I had delivered them – were now adults, some even parents.

The waitress returned. Jerked into the present we ordered.

Girls Numbers Two and Three are sisters. I asked after their parents, immigrants, older than me by ten years, proud people, beavers in the general community and within their own. Mum was alive, still vibrant – ‘and fat, like all of us!’ Shrieks of laughter. And Dad?

‘Dad’s fat too, and dementing. The grog; it’s Korsakov’s.’ The speaker is Number Two, now a nurse. In the care of their aging parents she’s the officer commanding Number Three and their brothers.

Both Three and Two were married when I last knew them. They’d married matching buffoons, agreeable blokes when sober, not often sober, not often enough agreeable. Three spoke: ‘Even before we married I saw how my father in law treated his wife. He’d tell her she was stupid, shout at her to shut up when she spoke. One time I saw him belting into her – he was full as usual. I froze. We never saw that. Mum and Dad would drink a couple of gins after work but they never got nasty. Not like that.’

Memories returned to me of the mother in law. A tall trembling lady, her face pink and scarred, she’d address me in a soft trembly voice, describing symptoms I could never fathom, never cure. Now I understood.

‘It wasn’t too long before Robbie was getting aggressive like his Dad. He’d go to the pub after work, get full, drive home drunk. I had my first girl, then the second. I thought, “No. This isn’t what I want for them, not what I want them to see.“ I rang Robbie and I said, “Don’t hurry home you drunken bum. Your wife and your kids have split.”’ Peals of laughter from Three, far the widest at our table. ‘Did he ever hit you?’ – I wondered. ‘Lot’s of times, but I’d belt him too!’ More jolly mirth. Three sits opposite me, her great arms a gallery of art in brilliant reds. Finer tattoos crawl upward from her bodice, another spiders around her neck.

‘Weren’t you scared, leaving him?’

‘No.’ The thought is a stranger to Three. She stares at my unexpected question. ‘There was no future there. I got up, took my girls and went.’

Did I raise an eyebrow? I certainly wondered at her resolve, her clarity. Her fearlessness. ‘Yeah, money was tight. I got a job and I worked and I looked after my girls. They’re good. Their blokes are lovely. And the three of us, we’re very close. Like me and sis here.’ The two women looked at each other and smiled.

Two reminded me: ‘I was a mother at nineteen. Got married. You delivered my babies, Howard. I was in labour, terrified, not knowing anything. You got up on the bed beside me and stroked my back.’ Did I? Nowadays the Medical Board would caution me for this sort of thing. They’d require me to undergo Education.

Two continued: ’You know everything about us. You’ve seen all our vaginas!’ Careless in their merriment the girls showed none of the self-consciousness that saw me look down and blush. ‘I’m diabetic now,’ continued Two. ‘But I’m good. After I left my husband I worked as a nurse, you know, State Enrolled. When my kids were adult and near-adult my partner encouraged me. He said, “You’ve always wanted to study. Do it.” So I did. I studied nursing at Melbourne University. Boy that’s a gap – from Victoria Uni to Melbourne. But I did well…’

‘Got Distinctions’, Three’s voice was proud.

‘I did all of it on scholarships. I had to perform. They can take the scholarship away if you get bare passes. Now I’m specializing in Mental Health, in charge of the ward. I love it.’

Three told me how she too had always worked in health, in administration. She described without bitterness how, after eighteen years, her institution had managed her out of her job and into retirement. ‘Now I write poetry. I go to Creative Writing classes. And every Wednesday I post a poem on Facebook. Wednesday is the hump of the week. I call my readers, my “humpies.” Here’s this week’s poem’. Three handed me her phone where I read her tidy quatrains. The verses spoke in anticipation of this gathering, in praise of the poet’s doctor, his kindness, his understanding. Blushing again I came across a ‘Like’ in response. The author of the Like was Four, another ex-teenager whose family I’d been close to. Four wrote, ‘I remember how Dr Howard comforted me when Karen died.’ Another thump.

I remembered Four, a striking girl with olive skin, tight black curls, a smile that made you feel like singing. I remembered Karen, Karen who was lost, that sparkling child. Karen was in the car that drove to the pub in the bush hamlet twenty kilometres distant from my country practice. The pub filled the young driver up with grog and watched him drive the carful of friends home. How many died when the car missed the bend? Four? Five? Karen was extinguished in that crash. I remember speaking afterwards with Four. Was she the only one I was trying to comfort? I think I was trying to comfort myself too. A year or so later another young driver killed himself driving home from the same pub. His passenger suffered a fractured neck, became quadriplegic. From that time until left I doctored the human wreckage. And my rage burned against that pub. I nursed a futile wish to close it down.

***

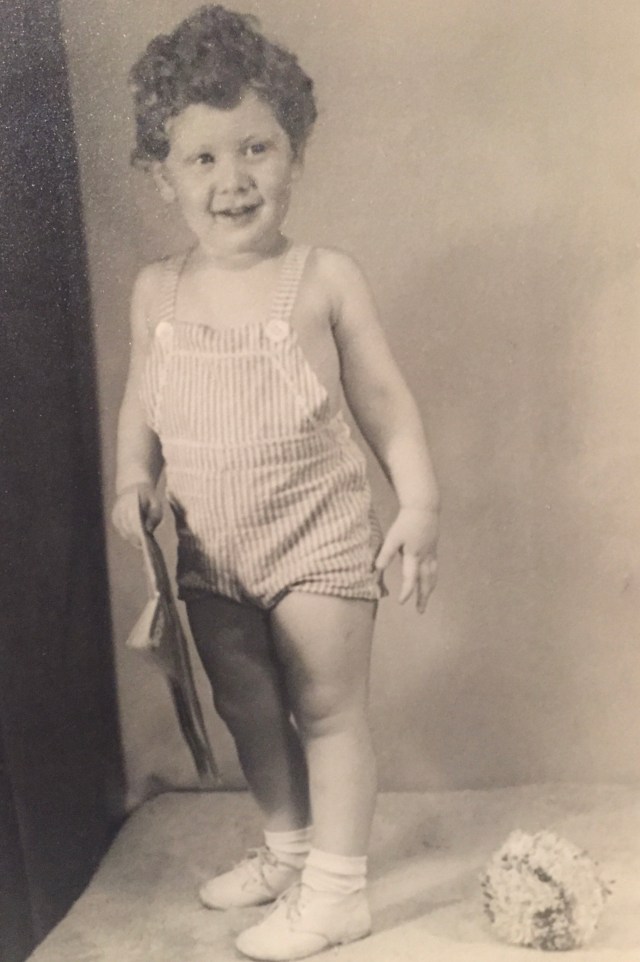

The girls spoke of the men in their present lives. Annie had formed a lasting union with Ian that prospers still. She showed me the album her family made for her fiftieth birthday. Here were Annie’s mum, Annie at fifteen, Annie’s own grown children, Annie with Ian. I saw a tall man, angular and strong-looking, with a craggy face. Two and Three spoke warmly of their own blokes. All three had known some duds but the ‘girls’ bore no hostility to the male race. When, at the conclusion of the evening, Ian turned up to drive Annie home he towered over me. My not-small hand was lost in his handclasp. Instantly likable, solid as a wall, he smiled and I felt gladdened for Annie.

Two asked Annie: ‘Have you ever seen your father again?’ Quietly came the reply: ‘I always vowed I never would. Then four years ago he wrote to me, to all of us, Mum, my sisters. He said he was dying, in Mallacoota. His heart was failing, from the grog. He wanted to see us. Mum wouldn’t come, neither would my sisters. But I thought, “He can’t hurt me now.” So I went. He talked and he talked, poured out his side of our lives. He lay on the bed and asked me to lay by him and cuddle him.’

I looked at Annie, my eyes wide.

‘I thought, “He can’t hurt me now. He’s old and he’s dying alone.” He’s got a partner but she’s not his blood. It’s not the same. I climbed up beside him and I held him. We laid there together for a good while. After a couple of days I went home. He died two weeks later.’